Isaac Stern – a timeline

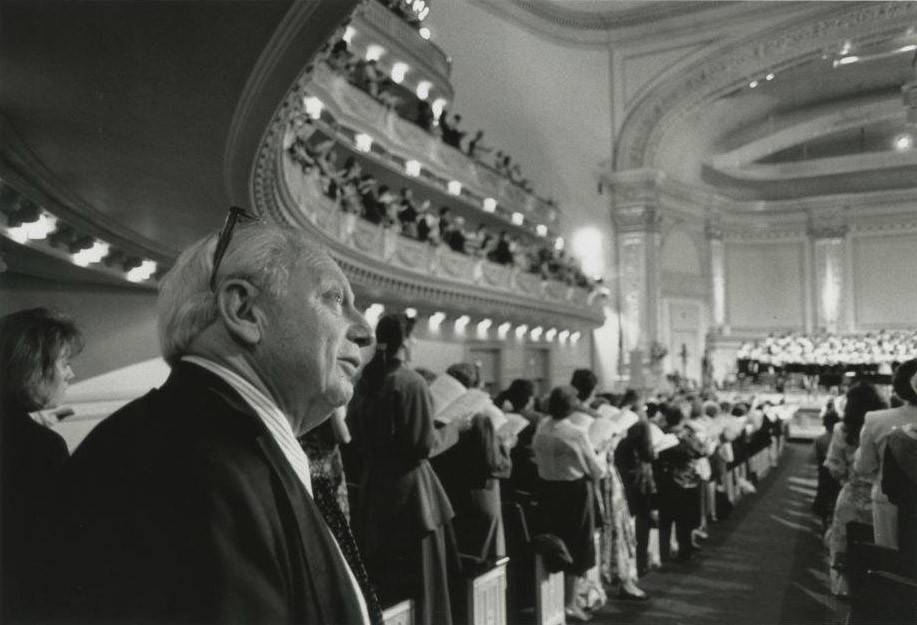

Remembering Isaac

By Gino Francesconi

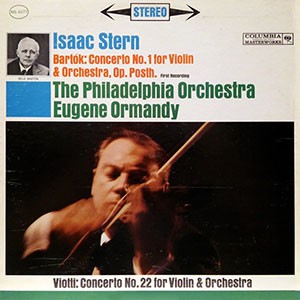

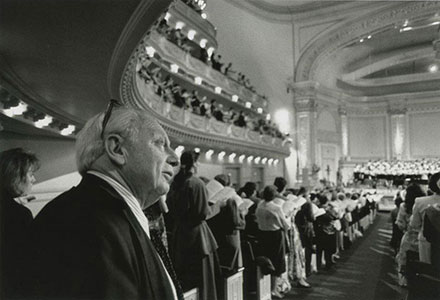

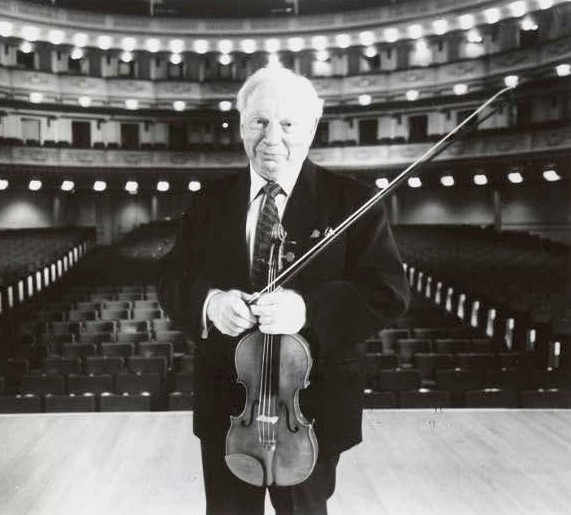

Isaac Stern was born on July 21, 1920, in Kremenets—at the time, a city in Poland, now in today’s Ukraine—and immigrated to San Francisco with his family when he was 10 months old. Isaac was not a child prodigy on the violin—in fact, he didn’t touch a violin until he was eight, primarily inspired by his best friend who played the instrument. But it was obvious from the start that Isaac had an extraordinary talent. His first public performance was at nine, his recital debut at 11, and at 17 he performed the Brahms Violin Concerto with the San Francisco Symphony—a concert that was broadcast across the country. At 23, he made his Carnegie Hall debut to rave reviews.

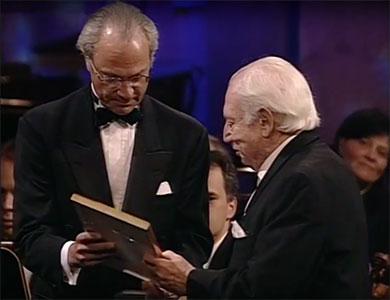

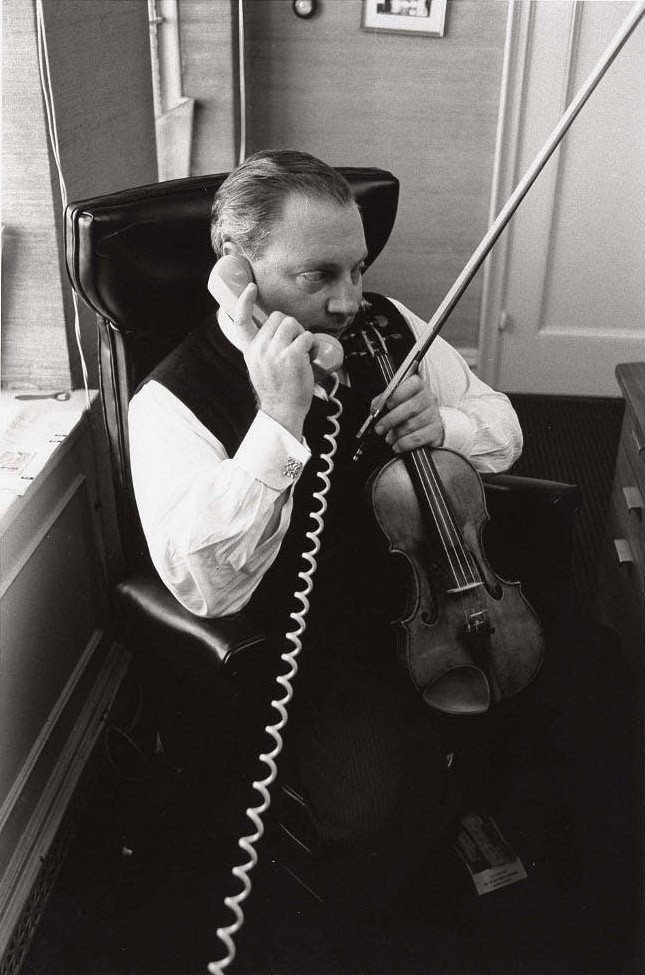

Isaac toured nearly nonstop, performing more concerts in front of more people than any violinist of his day, creating (as he called it) “a network of friends.” He premiered, commissioned, and recorded more new works than any other violinist in history. In addition to his artistry, the husband and father of three also gave generously and passionately to numerous causes. His agent, Sol Hurok, complained that when Isaac wasn’t on stage, he was on the phone. Conductor George Szell lamented Isaac could have been the greatest violinist after Jascha Heifetz, but he was “wasting” his time on so many worthy causes. And worthy indeed: Isaac was a founding member of the National Council on the Arts, National Endowment for the Arts, and Jerusalem Music Centre; president of the America-Israel Cultural Foundation; a mentor to many young musicians, including Emanuel Ax, Yo-Yo Ma, Midori, Itzhak Perlman, and Pinchas Zukerman; and the instrumental force behind the saving of Carnegie Hall.

Isaac Stern was 39 when he led the successful campaign to save the Hall from demolition in 1960. After convincing the City of New York to purchase the building, Carnegie Hall became the first structure in the city saved for its historical significance. Isaac envisioned that the Hall could serve as a national center for music education and the training of young musicians. The nonprofit Carnegie Hall Corporation was formed, and Isaac was its president for more than 40 years. In 1997, the Main Hall was named in his honor.

The hub of Isaac’s activities was his office—a large apartment on Central Park West. Everywhere one looked, a visitor’s eyes landed on an achievement: Grammy Awards on bookshelves; an Emmy on the mantle; an Academy Award on a table; artwork for a recording cover signed by Marc Chagall; dozens of photos on the walls, many autographed by such luminaries as actress Joan Crawford, composer Jean Sibelius, Secretary-General of the United Nations U Thant, and presidents from Kennedy onwards. There were numerous keys to cities, honorary doctorates from schools like Oxford and Juilliard, boxes of medals from the Presidential Medal of Freedom to France’s Legion of Honour, stacks of correspondences, and music neatly stored in cabinets and piled on the grand piano. Large filing cabinets filled one bedroom and boxes of files filled other rooms. And the phone lines never stopped ringing: “Mr. Stern, Senator Javits is on line two.” Then there was the privilege of seeing the temperature-controlled closet that held the priceless violins and bows, including the Guarneri del Gesù that belonged to the great Eugène Ysaÿe, who had inscribed the inside in French: “This del Gesù was the faithful companion of my life.” Isaac said he would add, “Mine, too.”

Isaac Stern died on September 22, 2001, at the age of 81. His tombstone in Gaylordsville, Connecticut, is marked simply: “Isaac Stern, Fiddler.”

— Gino Francesconi is director of the Carnegie Hall Archives and Rose Museum.

This article appears courtesy of Carnegie Hall; Clive Gillinson, Executive and Artistic Director

It was originally published in Carnegie Hall’s September/October 2019 Playbill.

Musical Ambassador

When Isaac Stern was 36 years old, he toured Soviet Russia in 1956, which marked the first time he would act as a cultural ambassador. He played in a number of venues and, significantly, he fielded questions from the stage after his performance in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory. That he did so in Russian, as a representative of the American school of violinists, was an act that endeared him to Russian musical audiences immediately. Upon his return to the United States, he spoke about the music worlds on the two sides of the Cold War. He talked much more about his respect and admiration for the colleagues and audience members he met during his visit rather than focusing on the material differences between the musicians in the US and Russia.

In an interview in 1956 for WQXR he said: “ To say I am an expert on all Russian problems would be fallacious…but from what I saw, the work that has been done to support musical efforts is an answer not to a political credo, but to a need of the people themselves. They live with music… This must be emphasized: … we in the West have a responsibility to see that they know about us as much as is humanely possible, in terms that cannot be perverted by a different political intent. This is the thing which I think we can say to them: this is what we believe in… this is our dignity and our belief in the human spirit in terms that you don’t have to say in words, [but] by playing music.”

His deep belief in the power of music guided him through his life and his career. In Israel he heard and nurtured the talent of a whole generation growing up in a new country, trying to find its voice and identity. While his decision to remain on stage to play Bach to an audience wearing gas masks during a missile attack in 1991has become his most famous moment there, it is the constancy of his yearly visits, listening and working with new talents that marked his most enduring contribution to the country. His creation of the Jerusalem Music Center remains the living testament to this legacy.

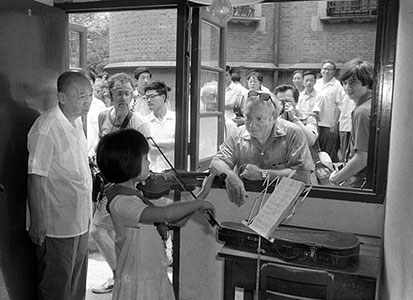

His visit to China in 1979 marked the beginning of the country’s departure from the horrors of the Cultural Revolution and its reopening to the world, which also brought a renaissance of cultural activity. His desire to go to China at that period was driven by an intense desire to understand a society that had been closed off. His approach was not one of demagoguery to explain western music; rather, he wanted to connect to the musicians he heard through the language that has no barriers, and in doing so, he managed to share his deepest credo, which still resonates there today. The gratitude is palpable 40 years later. If musical ambassadorship means true exchange and mutual respect, then Isaac Stern personified it at the highest level.In the academy award winning movie “From Mao to Mozart” he proclaimed, “if I have been critical, it is only to share…my faith, my abiding belief in both music and young people, and I believe between the two of them the world is a better place. And if I have left that behind, I will be very grateful.”

Activist

Stern the musician was also very much Stern the activist, focusing his energies on several important causes. He is best know as having spearheaded the saving of Carnegie Hall when it was slated for demolition in 1960, later becoming president of the institution. Stern’s ability to rally people to the cause of teaching music to young people led to his push to require teaching classical music to students in all New York public schools. As a result, he was also instrumental, with colleague Arnold Steinhardt, in bringing the groundbreaking violin program from East Harlem, Opus 118 to Carnegie for Fiddlefest, which allowed the program to continue in public schools. The story became the movie, “Music of the Heart.” Stern said, in a 1999 interview with Leonard Lopate of WNYC, “The whole idea, which I did not realize was driving me… I did things instinctively…I felt these things were important. That the quality of life depended to a great degree on how young people and young minds were given the opportunity to recognize what beauty there can be in creativity, which opens their own minds.”

Isaac Stern always had a strong connection to Israel. He became the founder and chairman of the Jerusalem Music Center, giving master classes and workshops and encouraging other artists to join him in his efforts as coach and mentor. In the same vein, he became president and chairman of the Board of the America-Israel Cultural Foundation, which gave scholarships and instruments to young Israelis studying both in Israel and abroad. Many of today’s major talents were early recipients.

Although Russian by birth and cultural ambassador to Russia during the Cold War, he later boycotted the Soviet regime, campaigning against Soviet opposition to the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1974. He returned after 1997 with the dissolution of the USSR, proclaiming, “I am glad to meet the Muscovites again.”

Stern would always quip: “I don’t worry about the Minister of Culture, but I do worry about the culture of the Minister.” His passion for promoting culture in the United States led to his organization and founding of the National Council on the Arts, a program that evolved into the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) under President Lyndon Johnson. “We can sing, act, pray and do many things with music and all without one word. That is its real magic.

Stern voiced his political opinions in support of a boycott against a Greek military junta in 1967, and in deference to survivors and victims of the Holocaust, never played in Germany.

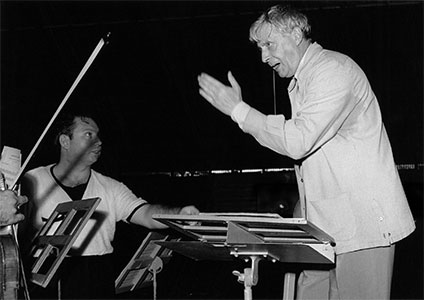

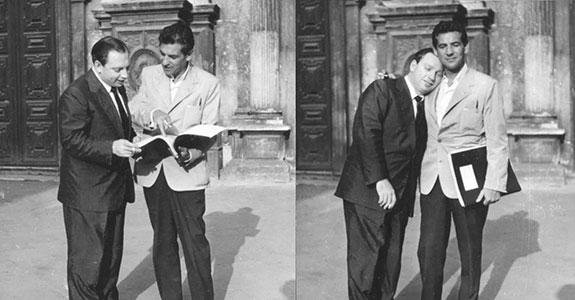

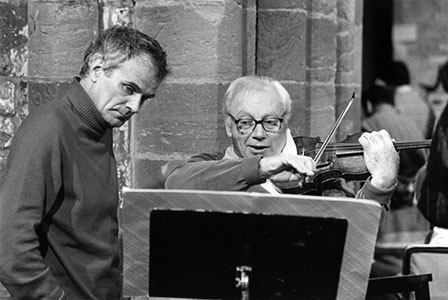

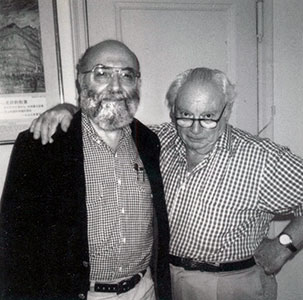

Mentor

Among all of Isaac Stern’s lifelong passions and commitments, none was more compelling, had a longer impact, or was more gratifying to him, than his mentorship of young people and the next generation of young musicians. He never held any official post, either privately or at a school, as a formal educator; and yet, he was an unusually effective communicator and insightful teacher, both technically and musically. “Don’t use music to play the violin,” he would always preach; “use the violin to make music.” This philosophy best explains why his profound influence remains with so many young musicians, and not just with violinists. The list of the names whose lives intersected with his speaks for itself: Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zuckerman, Yo-Yo Ma, Midori, Vadim Gluzman, Cho-Liang Lin, Sarah Chang, Jian Wang, Shlomo Mintz, Yefim Bronfman, Jaime Laredo, Miriam Fried, Sergiu Luca – and those few only scratch the surface. In master classes, in private encounters, in chamber music workshops, he always had time to listen, to advise, and to encourage. His intent was abundantly clear when he said, “ It’s the most wonderful thing in the world to see young people, to touch them with music …to open their ears, to make them hear not what they’re doing but what is possible, what might be done, what might happen, and that they can do it.”

His belief to pass along to the next generation as much as he could was an intrinsic part of who he was as a musician.

He was grateful to his formative teacher Naoum Blinder, the concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony, for having taught him what he considered to be the cardinal imperative of good studying, and by extension, good teaching. “My goal,” he always said, “was to try to teach young people how to teach themselves.” In the end, he was always consistent, in his playing and in his instruction, “to find the music between the notes.”

In addition to his keen sense for discovering talent, he was also focused on transmitting his core values. To the New York Times in 1979, he offered this assessment: “Most people, particularly some of the young ones today, don’t remember my apprentice years… I played seven concerts the first year, fourteen the next. I traveled in upper berths in trains. I practiced day and night. What did I know from Carnegie Hall, from arts councils, from big interviews? I worked my head off. Do they think that went for naught? I had a tough, hardening apprenticeship. It taught me the value of values.”

He approached the next generation with complete generosity and without any competitiveness. One year before he passed away, he affirmed his role as a mentor:“ I first heard Yo-Yo Ma when he was six years old; I first heard Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zuckerman when they were 10 years old. I’ve always heard gifted young people at all times and all over the world. So it became a natural thing, and I think later on I realized it was much more. It took many years for me to realize why I was involved. It’s just a sense of being grateful for what I have been lucky to have.”

ISAAC STERN and Carnegie Hall

By Gino Francesconi

Imagine you are passing a tall skyscraper on the corner of West 57thand Seventh Avenue and you see a plaque upon which is written, “On this site once stood Carnegie Hall, one of the most famous concert Halls in the world.” Today, that is fantasy. Many people are unaware that, in 1960, Carnegie Hall was nearly demolished.

Isaac Stern stepped in at the last minute and did something no one else had ever done. He convinced the City of New York to purchase a building for its historical significance. The general mindset at the time was that old buildings came down and new ones replaced them. Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts was going to be the greatest cultural center in the world. Carnegie Hall was 70 years old and in need of repair.

Isaac couldn’t bear the thought of Carnegie Hall being destroyed. “Like tearing down La Scala and replacing it with a garage,” he said.

The City of New York created the nonprofit Carnegie Hall Corporation with Isaac as its president. Just as Andrew Carnegie’s vision chose the location that seemed far uptown at the time, Isaac Stern had ideas of what Carnegie Hall could become. He saved it and then set wheels in motion to change it forever.

For its first 70 years, Carnegie Hall was simply a rental venue. After the Hall was saved in 1960, Isaac and his Citizens Committee to Save Carnegie Hall, chose board members, such as Marian Anderson and Eleanor Roosevelt, hired staff, some of whom began producing the Hall’s own events and children’s concerts. Discussions for much-needed renovations began, more funds were raised, and the Hall’s first endowment was created.

In the 41 years Isaac was president of Carnegie Hall one-third of the events became Carnegie Hall presentations, children’s concerts were joined by a series of Professional Training Workshops that pointed the way to today’s Weill Music Institute. Since then, the entire building has been renovated and reclaimed in ways not even Andrew Carnegie himself could have imagined.

– Gino Francesconi is director of the Carnegie Hall Archives and Rose Museum.

Link to Isaac Stern page on Carnegie Hall website:

https://www.carnegiehall.org/about/history/carnegie-hall-icons/isaac-stern